CONTROL

Reconsidering the designer as one among

many in a creative and collaborative network

of active participants full of agency and potential.

In these most depressing of times, these are some of the issues I want to press, not to depress the reader but to press ahead, to redirect our meager capacities as fast as possible.

—Bruno Latour

Abstract

My MFA work explores the creative networks between a graphic designer and their collaborators, both human and non-human (other designers, but also software, papers, inks, presses, cameras, the internet, design history, cultural knowledge, language, etc). My thesis project examines how the interplay of control and trust in a designer’s relationship with their network of tools (creative, cultural, technological) can be attended to, challenged, and reimagined. The black boxes which envelop our tools obscure the complexity and scale of the collaborative and relational space we work in. My work reconsiders the designer as one among many in a creative and collaborative network of active participants full of agency and potential.My thesis seeks ways to give the tools of my creative network fully agented status as collaborator by foregrounding instead of avoiding their active participation in what we create together. Through coding in various languages (javascript and Processing programs, InDesign scripts, and machine learning models) I created new digital tools in which the agency of the tool itself is highlighted. I use these new tools to undertake an intentionally nonhierarchical mode of making, decentering my role as designer to create a vast and potentially endless series of posters, zines, album covers, music, and poetry. Each of my projects pushes me further away from a mode of control towards one of care and trust in the creative design process, anchored in a belief that as long as there is collaborative care, respect, and trust (love?), the work we make together is worthwhile.

INTRODUCTION TO CONTROL

This thesis is about control, trust, and care in the creative process of graphic design, and about how trusting and caring for the network of collaborators, human and non-human that we work with can make a space for new kinds of work, exciting, unique collaborations that interact with the world in new ways. Through this reexamination of the role of the designer in the networks of actors that our industry exists inside of, we might find ways to accept change, to see failure in new ways, to find new energy of purpose.We seek control when we are more afraid of possible outcomes than we are excited by them. This fear of the unknown, fear of possible failures, fear of not having all the answers, this fear comes when we do not trust our team, our collaborators, our networks involved in our creative endeavors. But if we can show care (love?) for the actors in our networks (human and non-human), if we can trust that we are doing something worthwhile together, we can accept them and trust them. When we can do that, we can let go of the need for control, and we can leap with creativity, we can be the lightning of possible storms, we can light fires and be generative.

This thesis is structured around a series of essays that explore a set of design projects executed over the past two years for this MFA program. They chronologically trace the path of my personal relationship with graphic design (from feeling disillusioned and burnt out to finding a source of excitement and energy and care), my need for control, my fear of failure, my understanding of my role as a designer, and my gradual acceptance of a careful trust and trusting care of my collaborators (human and non-human).

The first essay, Camera Obscura, is about an ongoing photography project I set up in a converted attic bathroom during lockdown. The project’s key learning outcome for me was around a realization that this process was happening without me. The time spent sitting in the dark while my eyes adjusted to the relations between bent and reflecting photons and the substrates of the bathroom was a revelation in creative relationships that don’t center around me. A slow reveal that took time to grasp, but happened because I had the time to spend within this creative network of things that aren’t me, my role limited to setting up and documenting what they were up to. This was a first step in decentering my role, a step that was about seeing a nonhierarchical network of making and signification; seeing my place in it in a new light.

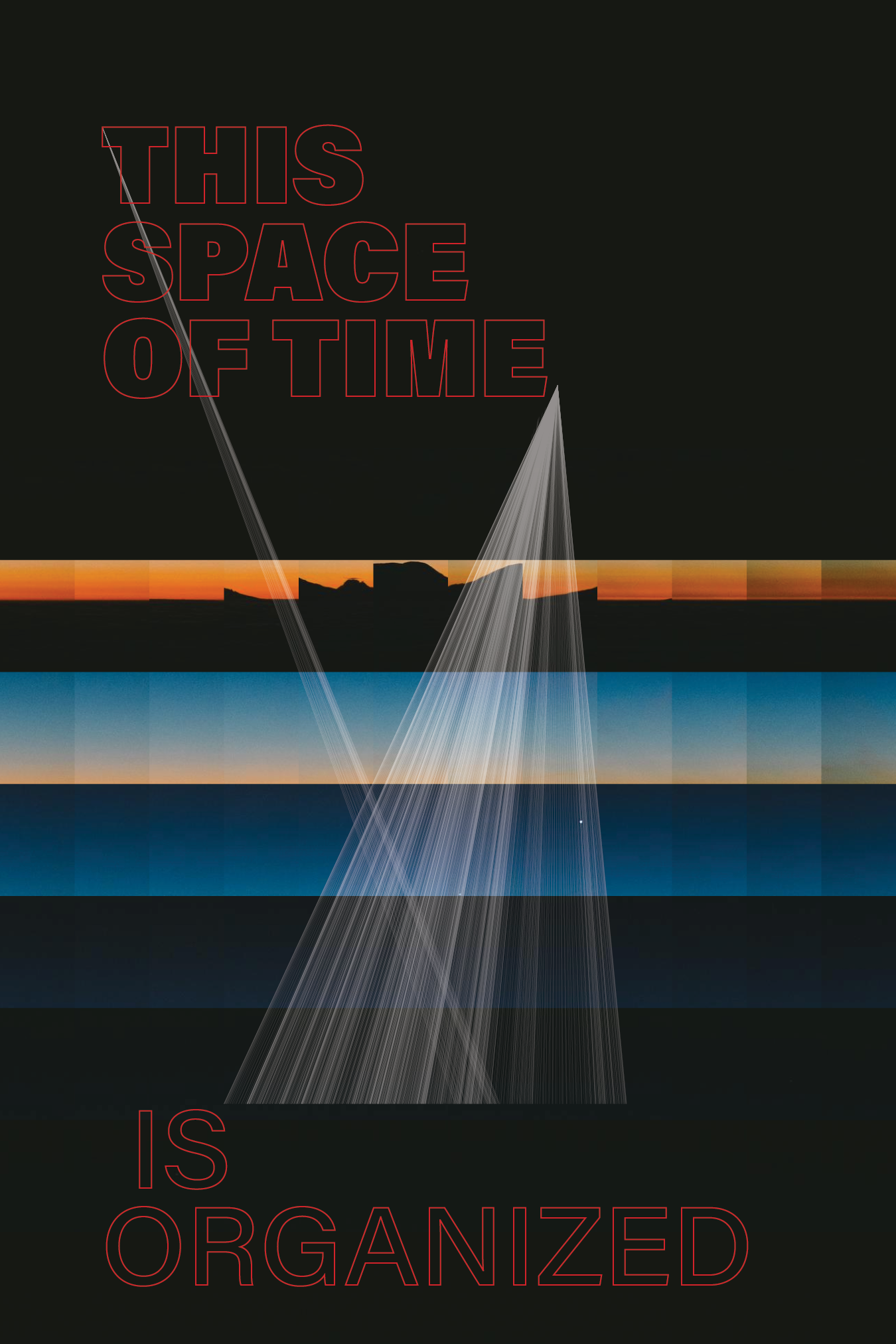

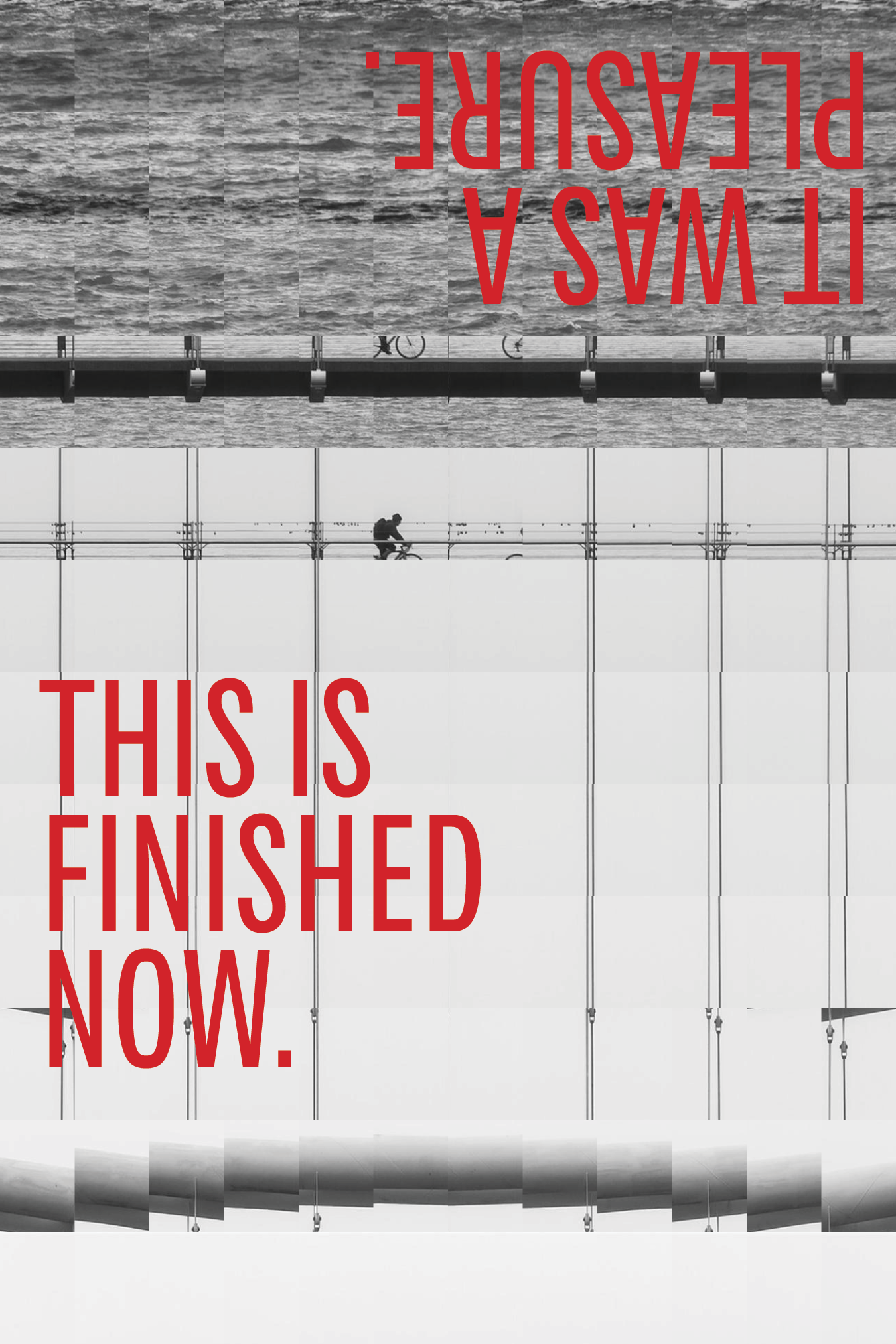

Chapter 2 — Hybrid Posters is about my early explorations with tool agency. In my previous work with letterpress printing, I had come to a belief that I could never truly master my working relationship with the press. I could learn its nuances and work with them, as long as I could give up on perfection and accept that I would need to collaborate but not really control the entire process or the outcomes. I could try to make exact copies, but variation was built into the work. It did not see it as a flaw but as a feature, worth attending to. I wanted to achieve something like that with my current, primarily digital tools. I wanted to give agency to my tools. I was looking to work with them, not to control them completely. I made headway into this by learning to code in a couple of languages that could help me tease open the software of the profession and bring in something like agented action. I found delight in some of the things I helped to create with these tools and these collaborative creative networks. I created new tools, modified old ones, and collaborated in a way with the network at play in these creations.

Chapter 3 — A Careful Trust / Zine Collaborations is about the process of collecting all of the prose, code, and images that I had been creating and making something new with it. Something that could highlight the year of work, and hopefully begin to make sense of what I was doing. I looked to find ways to alter my role in the process of making, spaces that could be played with in new ways, rules that could be bent, rules that could be broken. The essay considers ways that I might be able to let go and trust that we (myself and my nonhuman collaborators) are doing something interesting, together.

Chapter 4 — Dragons and Princesses is about my first encounters with machine learning and artificial intelligence. In previous projects, I had introduced a kind of agency through randomness that the programs I had written could act on. While they produced new and often delightful outputs, they were still only able to develop along lines that I had determined. They could only act as freely as I let them. Machine learning let me explore another avenue towards the collaboration I was seeking. This would be an exponential jump in scale and complexity in the network of collaborators. This would be truly new. And these projects all failed. I did not trust these tools. I did not understand them, and they made me nervous and uncomfortable. I withdrew my care. I pulled back from what I thought might be monsters.

Chapter 5 — Floating on Oceans. This essay documents my early explorations of generative machine learning models. The previous AI and ML projects I had worked on were based on the “detection” side of the models. They had been trained on huge datasets of images and could determine the content of new images with remarkable accuracy. They are often brutally flawed. I had abandoned them and their fraught ethics. The models I wanted to explore now could make amazing things. The StyleGAN model from NVidia was producing remarkable outputs depicting people’s faces, but people that did not exist; newly generated faces that looked so real that it was hard to comprehend what you were looking at at first glimpse. I hoped to find similar success making new graphic design pieces with similar ML models. This essay explores three attempts at working with GANs, each a fantastic failure and success. These projects were the first glimpses I had at the scope and complexity of what these models were producing. These projects all produced incredible things, but I could not understand their aesthetic value at the time. What seemed like failures at the time were, in fact, only failures in my ability to see or understand what I was looking at, at what I was experiencing.

Chapter 6 — Infinite Art Bot is about the creation of a nearly autonomous art making bot that posts to social media platforms. This project was about an exploration of the massive networks that these projects interact with and collaborate with and about a real attempt at letting go of control, trusting, and caring—trusting the collaborators, and caring for (carefully attending to) both the process and the result. The bot was a months-long programming project that was the most complex arrangement I had worked on to that point. It brought into play all of the things I had been working on and with for the past year. It just needed a little nudge from me to get started, and then the network of agents pushed and pulled on each other, added and multiplied what each had to offer. We did and made the most amazing things.

Chapter 7 — CONTROL V1 a booklet about care. This is an essay about teams, networks, and finding the thing I was looking for in all of this work and making. The entire process from learning to code simple five and six-line programs in Javascript to working with the most advanced language models available (a university in China just published a paper about a new language model they made that is again a tenfold jump in scale and power from the one I have access to now) has given me new regard for the entire endeavor. I am excited about graphic design again, about what is possible and how we can communicate and grow through this visual and textual making. I have an entirely new outlook on the process of making that is grown out of a place of trust and care. I am not worried about machine learning’s impact on my work. I am excited to see where the team-ups take me/us.

Chapter 8 — Speculative Anthropology. This is the concluding chapter and project for this thesis document. This essay is about strange explorations of the latent spaces of machine learning. What can we find when we explore this sort of hidden and near infinite space that these networks allow us access to? This essay imagines a sort of exploration of possibilities never realized, a look at the objects we might find, a speculative anthropology of alternative histories that we might explore and learn from. And while maybe there are more significant concerns and uses of this sort of speculative research, they are not my interests. When I met HAL, I did not want to talk about questions of phenomenology. I wanted to make cool posters and start a cover band.

This thesis is not and was never about machine learning or artificial intelligence. I am not going to have a big reveal at the end where I explain that this was all written by a robot and you have been tricked in some manner. These are my human words, but I got to them in relationship with a decidedly nonhuman team of collaborators and makers. It has been important and valuable for me to examine my role in the creative process more deeply, to question what I have taken for granted in my two decades of work in graphic design, to think about these things we designers do and make in strange new ways. Not to confuse the issues with jargon and obtuse readings of ideas but to imagine what might be the results of thinking about our roles in strange ways through odd and unexpected new lenses. What if we are all part of a network and not at the center/top of it? What would that mean to how we work and what we value, to the stories we tell ourselves and each other about the work we do and why we do it? I think that these questions can help us prepare for the changes that machine learning will bring (is already bringing) to our world and our work. The impact of this technology is going to be massive, but it does not need to be devastating or displacing. We don’t have to be gatekeepers; we can be collaborators, with a say in what happens next.

“Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.”

—Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

︎︎︎︎︎

Next

Chapter 1 — Camera Obscura.

Chapter 1

Camera Obscura.

A second aspect of my experimental attitude involves speculation, and for me that means asking about the reality of the relations between things, relations that are not dominated by the human experience of those things. That is a hard task, for how do you imagine the relation between a snail and the leaf it is eating (which is perfectly real as a relation) without anthropocentrism, without scientific reductionism, even without language?

— Muecke, Stephen. “Motorcycles, Snails, Latour: Criticism without Judgement.” Cultural Studies Review 18.1 (2012): 40-58. Print.

A camera obscura creates a projection from light on the other side of an aperture. It shows the outside on the inside. The light that you might typically experience hitting your eyes is instead hitting a wall, a bathtub, a door, or whatever solid surface is there, and then reflects back into your eyes or camera. This adds an extra step, a step that helps create something new and unexpected.

This year-plus of lockdowns, shelter-in-place orders, and the sudden forced insideness of pandemic life has in many ways, more and more as I continue to think it through, made the meaning of this camera obscura project that much more significant and intense for me. I live in a small town in a low population area and see very few people (outside of my family) in real life. The images projected on the walls really do, in many ways, match my world. The upside down ephemeral images now seem right; they are an accurate reflection. This year has often felt surreal and incomprehensible.

This is how it works: light from outside a black box projects onto the wall opposite the aperture, creating an inverted image of that view. One of the interesting things I had not been considering was the nature of that “wall.” I set up this project in my mostly unused attic bathroom in our temporary on-campus housing, and I had very pragmatic reasons for it. It has only one window (so it is easy to set up the blacked out window; I covered it with cardboard pierced with one small aperture hole); no one in my family really uses this bathroom, so closing off the window doesn’t matter much (I had started this project in my home office but it was unbearable to be in that dark of a room for long); the room is pretty empty so the projected images are not obscured by the objects of our daily lives.

Deeper than that, past the pragmatic reasoning, I have made other choices that I had not given much consideration to. I could hang a sheet on that wall to create a clean and simple surface for the projection to show; instead, I am projecting on a wall with a door, a clawfoot bathtub, and a built-in storage unit. My wife commented that the photographs resemble something that David Lynch might make, in that they are surreal, unheimlich, uncomfortable, and sometimes maybe beautiful. The mundane everyday (but also mostly abandoned) space becomes elevated; the space is reconceived and made special in some way. Where a photo of my bathroom’s view of winter trees or a photo of my bathroom wall would not be interesting or worthy of much comment at all, the combination is something new, a bit strange, and strangely interesting. The materials, the process, the documentation, these all work together to make something worthwhile and maybe wonderful. I’m beginning to realize that all of my pandemic-thesis projects are like this.

The actions, or really lack of actions, needed to make this work—the sitting and waiting for your eyes to adjust to the light/dark of the room and the for the projections to become clear—reminds of a James Turrell piece viewed in a nearly pitch-black room that you have to just sit and wait for your eyes to see. I have entered one of these Turrell Dark Spaces at MASS MoCA, and find viewing it slightly uncomfortable. I start to get bored sitting looking at nothing, but then as I begin to make out something, it becomes clearer and more apparent, and I wonder how I didn’t see it before. The experience is something simple and maybe profound. The creative network of things (light, wall, bench; and then sometimes also eye, brain, me) has been there working together the entire time; it has not needed any audience to activate it in any way.

My camera obscura project is a collection and collaboration of objects acting as tools, acting with a sort of agency, and participating in a network of ideas and things and idea things and things that are ideas. Each time I go into the attic bathroom to take these pictures projected light bouncing off walls, or as I sit and wait as my eyes adjust to the dark, to the faint light of this process, I am merely observing something that is happening with or without me present. The light streams and the photons bend and bounce, creating these images whether I can perceive them or not. The light, the cardboard, the enamel of the tub, the paint on the walls, door and cupboards are all part of the network making these images in ways I can’t fully understand, sense, fully grab hold of or in any way define, but that I can be a part of and document some aspect of. Not all of it, but a bit of it. The tip of an iceberg of making. I only need to sit and wait and trust that something worthwhile is happening.

This is an ephemeral experience; it does not make a record, it does not leave any trace. I have to do that part. To document the experience, you have to use some kind of long exposure camera with something like film. My phone’s camera app has a machine learning enhanced Night Sight setting that functions similarly to a long exposure setting on a film camera.

Taking a picture with a camera while sitting inside a camera is an odd experience, like being in your car while traveling on a ferry. While not profound, unusual. When you pay attention to it.

The end.

︎︎︎︎︎︎

Next

Chapter 2 — Hybrid Posters.

Chapter 2

Hybrid Posters.

An essay about my early code based projects and attempts to let go of control, and collaborate.

In trying to make something new, in trying to define a new relationship with my tools, to unsettle and challenge what I was comfortable with as a maker/designer, I hoped to find something to be excited by. And maybe if I couldn’t find it, I could make it. I was bored of my tools, bored of the traditional outputs of graphic design, bored of how I worked, what I made, and how I saw the things others made. I knew the marks that our tools make—again and again and again—and found little interest, no pleasure, and an absence of surprise or wonder at almost anything I looked at (anything that was in the realm of graphic design anyway).

When I used to work with letterpress (on my own and while teaching a letterpress class at RISD), I had found a real sense of delight in that tool-designer relationship. It was fun and exciting to act against the weight of the drum physically, to feel and hear the paper crush under the pressure of the roller. To work and make with this massive and imposing machine and be surprised by the results. The new limitations and unknown (to me) possibilities of this work were fantastic.

But I also saw master printers create pages that bored me to my core. The ink “kissing” the page was considered “good” by those who knew what they were doing—counter to the vulgar deep impressions that wedding planning young people and millennial hipsters wanted to see. The limited-edition runs of great American novels or new translations of the Classics that sold on subscriptions to a small number of collecting libraries for thousands of dollars made me angry and annoyed with the people I met in the letterpress community and the types of work they found acceptable and unacceptable.

The excitement I felt for the possibilities of working with this capital-T design tool, matched and encouraged by the frustration I felt for the snooty and judgement filled rules and traditional outputs it was supposed to be used for, pushed me further into a space of experimentation. I decided to break as many rules as possible, stopping just short of breaking the letterpress itself. I came to seek this same expression, freedom, and novelty in my work with other tools. I started trying to learn code so that I would bend the rules of programs like InDesign. I used sound editing software to edit photographs. I used projectors and lasers to find new ways to interact with new substrates. And when it came time to choose a method and mode of work for my thesis project I decided that the most promising path forward, one that was well-tread and would be the easiest to navigate, was designing with code.

I spent hundreds of hours learning to code in JavaScript and Java (for P5JS and Processing specifically). I wanted to find a way to feel that sense of collaboration I had felt with the letterpress again. I wanted to work with my tools in some way, to try and listen to what they wanted, to let them make choices. I had broken the rules with the letterpress and ignored traditional practices in order to get to a new creative space. With code, I could repurpose a program and make it work differently to try to make something new. I could misuse it, break it, and learn from the breaking. I was interested in flouting and breaking rules again, in making things work counter to their intended or “correct” uses. And the space of coding did that; it opened up my creative making, my tool use, in new ways, and allowed me to create new things. But I was still very much in control of the outputs and choices.

A solution came in exploration of Surrealist collage techniques. The exciting juxtapositions that often stemmed from these chance-based techniques were something I thought could be expressed with code in a new and exciting way. And randomness is a way of giving up control over outputs. The math.random() function (or something very similar in each programing language) was the method I would use to loosen my grip, and try to introduce a sense of agency into my hopeful collaborations with code (code as tool; tool as collaborator).

The first steps involved adding a random display element to a coding tool that I could interface with and effect in some manner. I created a set of what I called “strange tools.” Most tended to act in this manner (example); a line was created between two points, where one point’s location on the screen is determined by me (usually through mapping mouse locations) and the other by an x and y coordinate using a random number generated by the program’s random function. I created dozens of these strange tools, each offering variations on this basic functionality.

This randomness could be applied to almost any aspect of creating an image with code. The dimensions of the canvas or output space, the size and scale of added objects, the number of those objects, the locations of them—these all could be modified in something that looked like tool-agency by way of randomness. The randomness did work to challenge my control over the outputs, but it was constrained. The strange tools typically only reacted to my prompts and did not act without a push of some sort. I was allowing for a kind of messy interaction, but one that I plan and that I, in the end, control.

So I pushed a little more, looking for a more authentic and non-hierarchical, even field of collaborative making. I hoped that the exciting juxtapositions of Surrealist collage techniques would create a less controlled output. Randomness was still my way of introducing something that could act outside of my control, but I would attempt to create distance from my inputs in these programs. The various collage techniques (cubomania, étrécissements, photomontage, and triptophraphy) could run as an algorithm of sorts. Each method had variables (i.e., the number of cubes) that could be given an upper and lower limit but be randomly picked by the program as needed. To push these programs further, I made the image selection itself a random process, adding randomness to the URLs used for the image archive sites. Many of these programs only needed me to hit the start button and would otherwise run themselves.

With the Surrealist collage programs and the strange tools, I created hundreds of images. They were exciting and unexpected. I developed many other tools and techniques that worked in similar ways towards similar goals. The outputs were excellent, and that really should have been enough. I had created a set of tools that acted with a version of agency that I found compelling and valuable. The collaboration was productive, and I was finding myself often delighted with the outputs—and this is what I wanted; to be surprised and delighted by what I had a hand in making. But I suppose they did not feel like “graphic design” in some way. I didn’t have to try very hard; the designs didn’t communicate anything obvious; they were simple and easy, and graphic design graduate school felt like it demanded more. I needed to show my mastery over the materials; I still felt that I needed to control the output and do the real making, if I was going to call the work mine.

In the final outputs of these projects, I treated the individual images as elements of a larger and more complex system. I created a set of hybrid posters featuring the collaboratively generated objects working together in various ways. Again, I exerted my control, this time as editor and curator. I determined the value and success of each of the elements and chose if I would include it in the final design. They are beautiful, a successful and prolific creative output, and maybe they are collaborative (with code/tool as collaborator). But they are still very much made by me, under my control as desinger-god working behind the screen to make a hopefully beautiful thing. And so, onto the next.

The end.

︎︎︎︎︎︎P︎

Next

Chapter 3 — A Careful Trust / Zine Collaborations

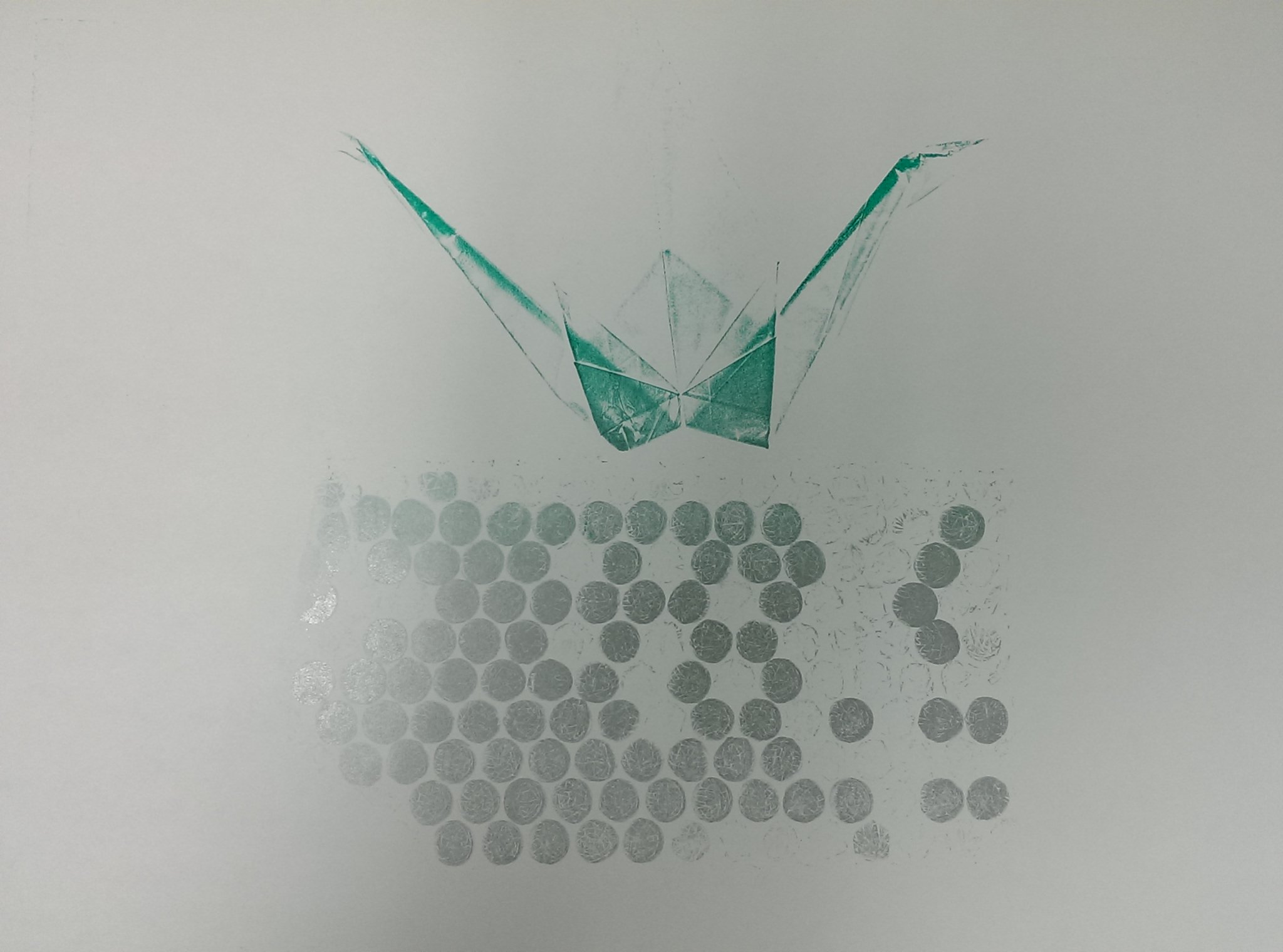

Chapter 3

A Careful Trust / Zine Collaborations.

An essay about the creation of a program that generates zines, and the first explorations of what moving from control to care might mean.

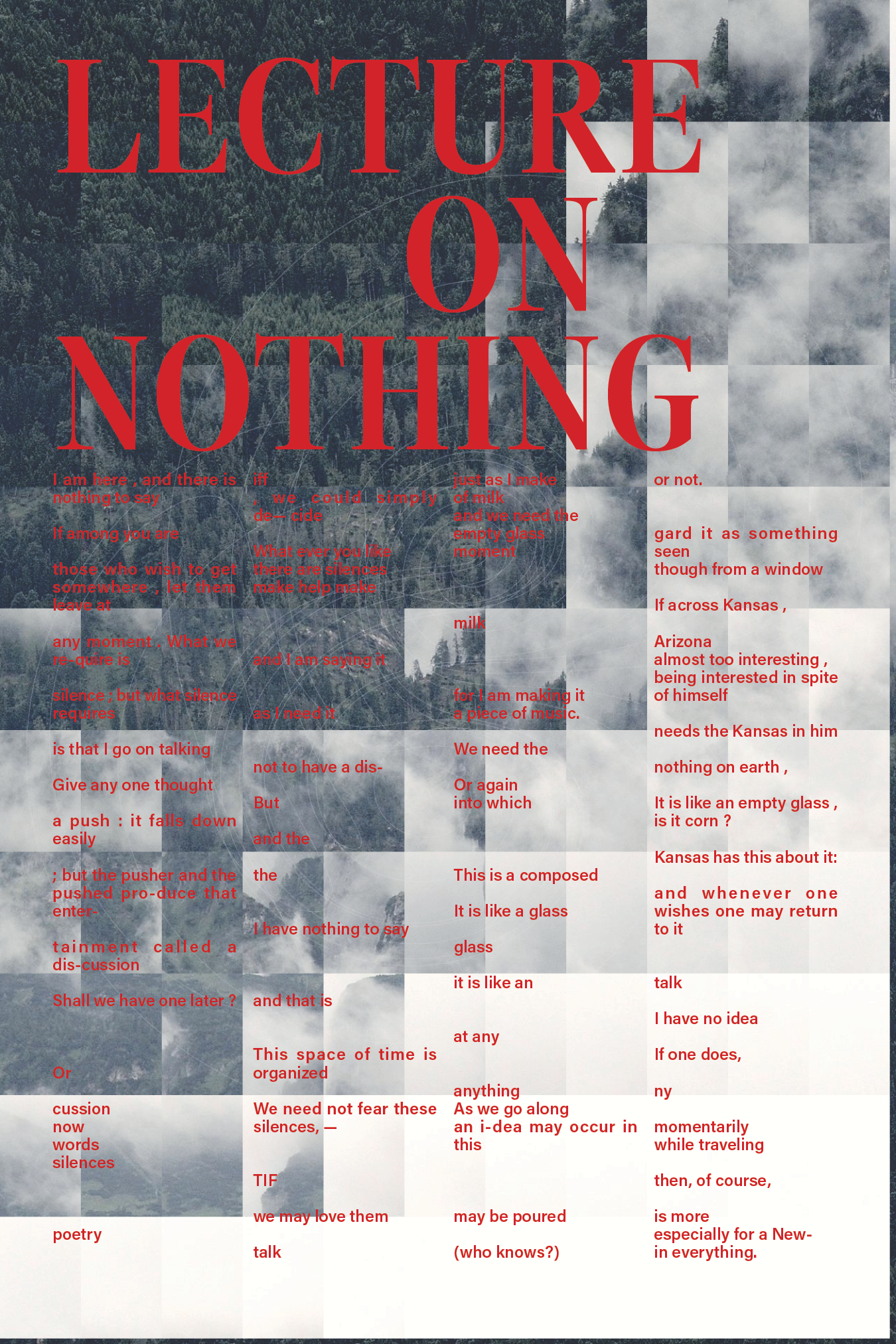

The final project I created during my second semester of work is a zine generating collaboration program that pulled together all of the technical code-based learning of the previous six months, and the writing of the six months before that (my first semester was spent writing with Natalia). This generative zine project is an attempt to work toward sharing creative credit for the projects I work on; pushing forward my initial interest in collaborating with humans, and more and more with non-humans—with my design tools. To make these generative zines I assembled the various parts—tools, ideas, data sets—set some parameters, and gave it a nudge forward. I produced three versions of the program, all coded in Processing.

The first uses a technique called ray-casting to display a simplified example of how light beams are cast around a space interacting with objects. Each zine page has a unique space and arrangement of various sized rectangles and a randomly placed circle representing the light source. The zine’s text comes from essays I wrote during my first semester, on a range of graphic design topics. Each page has one paragraph of an essay. The placement and dimensions of each text block in this ray-caster version are based on a randomly generated number with a minimum width. Each time the program runs and the network of things collaborates (text, image, page shape, code) it creates a unique zine. The range of possibilities is vast. The outcomes are PDF files: they are final, they can’t be edited, they are a collected output and a completed design object.

The second version of the zine collaboration contains a selected (by me) essay I had written, alongside randomly selected, scaled, and placed photographs. Each page again holds one paragraph; the dimensions of the text block are determined by a version of randomness called Perlin Noise. This kind of number generation picks a random number based on inputs from the previous number, generating something that looks a bit like a wave moving back and forth through space. In theory, these text blocks might seem more related in shape and area than with the previous total randomness of the first zine generator.

The locations of the text blocks and the folios rely on a version of a random walker. A random walker is a math-based example of random motion where each step can either be up, down, left or right. At each step, the choice is made again, creating something that has an uncanny naturalness to it, something planned but in a way or scale that is unknowable to me; something like the path of vines that have grown up a wall, or the spread of moss.

The version of a random walker that I set up in this arrangement is called a Levy walker. This kind of walker uses a model based on a foraging animal in nature. The walker stays in one area moving around in small steps and then makes large jumps to a new location to spend some time there looking around, foraging, sniffing, whatever it might be imagined to be doing, and then doing it again in the new space.

The photographs are linked from unsplash.com (a free website with an extensive archive of contemporary photos), because this website’s specific URL structure (ex https://source.unsplash.com/random/300x500) allows a random number to be added in the x and y values. Again in this version of collected inputs, the final piece is unreviewed, unedited, unchanged. Nothing is approved; the collaboration with the code is trusted to make something worthwhile.

The third version of the zine project combines aspects of the previous two. Each page’s text block dimensions and location are generated in some variation of randomness. Some rectangles and one circle are added to each page with almost every measurable aspect randomly generated. A similar photo selection is used, but all of the photos are converted to grayscale (converted by the program, because I told it to do that).

Each of these collections of ideas, methods, and actions produce a unique output: each and every zine is different from the last. Each is unique; changed; they are new. They repeat ideas or themes or aesthetics, and each time the program runs they are made anew, each run creating novelty. The space for this novelty is opened up and made possible as my expectations for what the outcome should be, what the page should look like, are erased, overridden (I’m sorry Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that)—or at least dimmed a little, as my control over the other actors in this production becomes looser, and my trust that we are making something of worth in this weird collaboration is slowly but importantly strengthened.

One of the aspects of this project that I find intriguing is the idea of potential possibilities: the many, many possible outcomes. I imagine the network like an atom—a collection of probability clouds, each element existing within its specific orbiting space. Like an atom, maybe, our observation of it changes it; we document it in a candid and unplanned manner—a series of snapshots of a river flowing, each one of the same river, but each different from the last and the next shot—potential, or real.

A complete inventory of the network of actors involved in the creation of my zine generation programs would, likely, in the end, stretch out to touch an awesome number of inputs spread out across disciplines, technologies, spaces, and people. The center of this project (as observed by me) is the program Processing (used to organize all of the elements of the program), the programing language Java (the language that Processing runs on), the website unsplash.com (for image selection), my essays (the written content of each of the programs), and the reader/viewer. Each of those elements is deeply complex, with rich histories and complex networks of relationships connecting to more and more similarly complex networks. Things reveal themselves to be more and more out of my control.

When considering this kind of collaborative making from a vantage point that decenters the graphic designer out of their (my) role as primary and sole author/maker, we (I) might be able to see ourselves as one among many. Sometimes small in context, occasionally massive, floating in an ocean affecting and affected by currents and forces we do not always see. But in this floating understanding, this unmoored space of ideas and things, maybe we can see that this is not a new or restructured hierarchy that has diminished us in any way, but simply a new view, cleared of our sentimental human-centric expectations, that values trust in collaboration and makes in relationships with our rediscovered collaborators.

The end.

︎︎︎︎︎

Next

Chapter 4 — Dragons and Princesses.

Chapter 4

Dragons and Princesses.

“Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.”

― Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

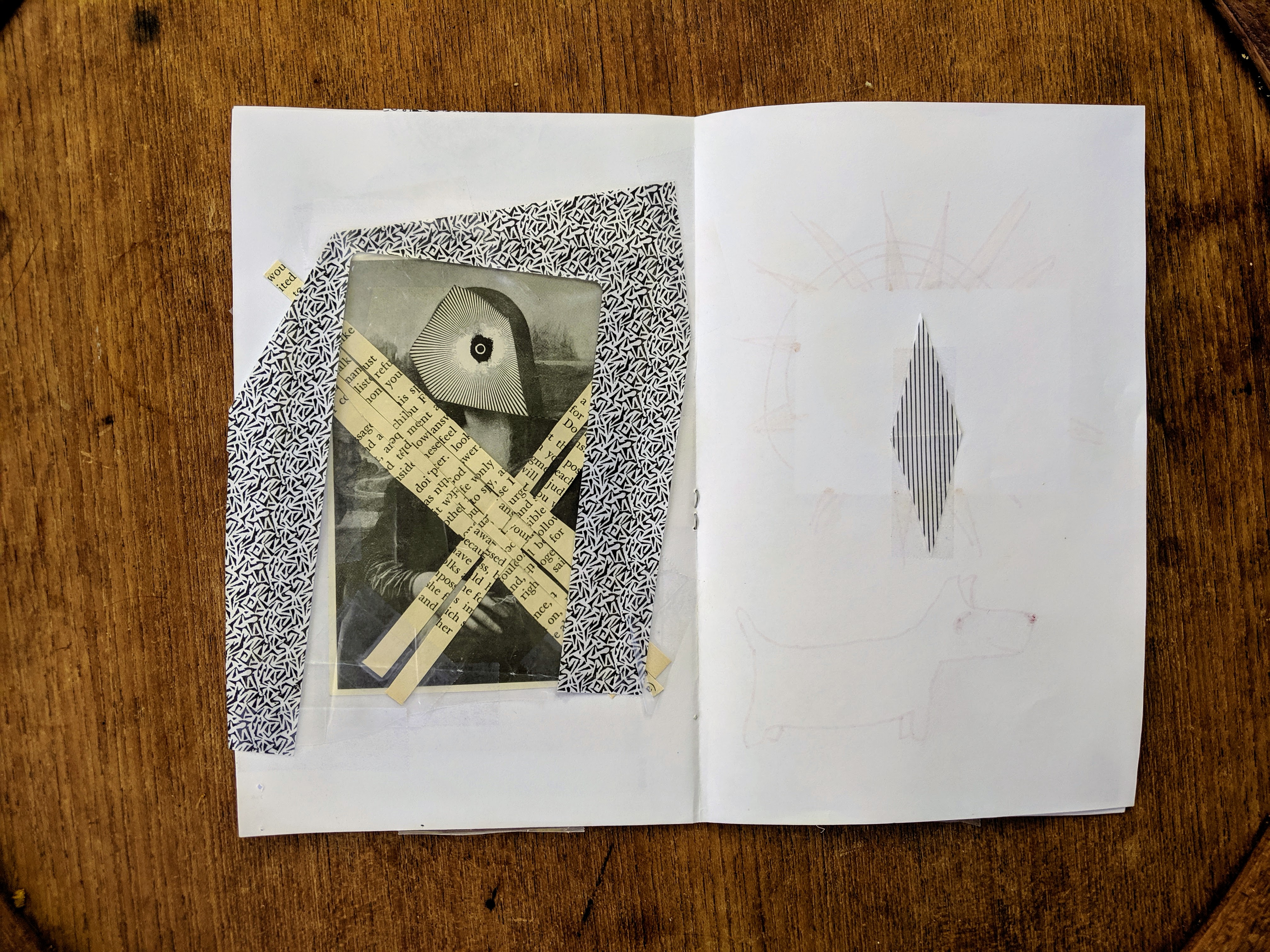

This essay covers a series of failed collaborations, confusing princesses for dragons.

In my attempts at unsettling my role as the natural and assumed center of the creative process, I added chance and forms of randomness to my network of tools. I included randomly selected lines of some texts, and loosened my grip on the specific numbers that needed to be included in the programs that affected the outcomes. I let go, but only a little, only within boundaries that I very deliberately set. Images were randomly selected (but from an archive I selected), the text block was randomly placed (but with parameters to stay fully on the page), the dimensions of the text block were randomly selected (but within a range that would prevent negative numbers and therefore backward text), the colors, the shape of the page, the overall aesthetic; all of it was at my direction. I had let go to some degree, I had loosened my grip, but it was still my show; the letting go was still well within my control.

The programs that I had been writing were self-contained and narrow in what was required of them. They incorporated code from various communities, employing solutions other coders had developed to problems I was facing. They occasionally reached out into the internet to download a photograph, but they generally existed entirely on my computer. What was achievable with chance and randomness was fantastic, and I had only really begun working in that space, but what I hoped for was something past chance. I saw the possibility to move past randomness towards real collaboration in a new set of tools: machine learning and artificial intelligence. I saw various ways to link up my projects—to extended the creative network of agented actors, to redefine what a collaborator was—to the machine learning tools that Google and others had been developing was being developed by groups like ML5. Using and collaborating with these tools I saw an opportunity to create work with inputs that had much more say than math.random() had been able to express.

<HI PERSON>

The first project was a failure, but I had set it up to fail. It was a failure in the sense that the output was clearly nonsensical, and I had set it up to fail mostly to make fun of it. The Bad Art Generator project uses a machine learning dataset called ImageNet (ImageNet is a massive collection of images tagged by hand that was used to train an image identifying algorithm) and a randomly selected photograph to create the output. The program downloads a random picture from unsplash.com and then the algorithm uses the ImageNet dataset to attempt to identify the subject(s) of the photo. What the algorithm can do is actually fantastic; its ability to even remotely identify the content and subject of an image it has never encountered before is a huge accomplishment. But it’s also often stupid and wrong, ridiculously so. It reminds me of a scene from The Simpsons episode “Last Exit to Springfield” (Season 4 episode 17): I am in the role of Mr. Burns chastising his monkeys for grammar errors.

The program’s image identification is often wrong; it is hamfisted in its reductions and assumptions, lacks any nuance or cultural understanding, and seems hopelessly foolish. It can be all of those things. It can also make something like a profound statement, making a connection I had never made, seeing something new and different in an image I did not care about, or think twice of.

This was my first exploration of a real letting go, of something like a collaboration as I have come to understand it. The implications of this scared me more than I had thought it would. The collaboration was there; I could have chosen to trust the process, trust the network, trust that we were going to make something exciting and new. Instead, I withdrew that trust and turned to easy laughs at the expense of the nonhuman I claimed to be collaborating with. I mocked it for not being perfect and sheltered myself from caring about the outcome by making its failure the point. The text at the top that reads “hi person, buy this” was decided on and added in by me (not generated by the code) in a mocking fashion, using the bland and non-specific language that can make ImageNet sound silly. “Buy this” was also used to make the output seem clunky, crude, and unrefined (the opposite of what I want people to think of my clever and insightful work.) I then dressed it all up in a sort of youthful pose of something that looks like graphic design. The acid green, the stroked text, the system default Helvetica; a bunch of graphic design looking stuff to distract a viewer from what I had actually done and my intent.

The technical aspects of the project are a very teamwork oriented back and forth communication (the team being me, the code I wrote, the image archive unsplash, and the machine learning dataset ImageNet). The code adds a random number to the URL that is passed to the image archive site, and then downloads the photo. ImageNet then makes a guess about the content of the image and returns a text array of likely terms and percentages related to that guess. The program then takes that text information and determines the maximum size of the text in the font I selected to fit on the final output size (the percentages are ignored).

The result is an intentionally terrible advertisement. If this project succeeds at something it’s making fun of AI, and also capitalism.

OBJECT DETECTOR LOOKING AT ARTS

This was an experiment in trust with the network and its actors/objects. In these projects I aimed the image selection at the MET’s online database of images. In the two versions discussed here I used ImageNet to run an image classifier in one and PoseNet (which attempts to build out a wireframe model of a person based on one image) in the other. In this project I never produced a final output that I would consider done, I abandoned the project before I got that far along.

These tools were fascinating to be using. Not many designers seemed to be working in this space, and it felt somewhat unexplored; it felt like I could try something genuinely new. But I was also afraid that in a new space where I could try and create something new I could also legitimately fail. In that fear of real failure, I again took control away from the network and my tool-collaborators. I still did not trust them. I was still testing them, and wary of them. I was looking for and hoping to call them out on their failures. I secretly hoped to show that my humanness meant something more when looking at art, that I would see beauty and be free of judgment about the limits of what is acceptable in shape and form. I thought I would catch the network in a compromised ethical space making assumptions and categorizations that would show that it was, in fact, monstrous and bad. I assumed AI and machine learning were dragons, and that my work would show that I was right not to trust in it. It would show that I was right to pull back my care, to take care, to tread carefully. Unsurprisingly I got nowhere.

FACEAPI HIERARCHY PROJECT – HEADLINE POSTER.

I abandoned this project because I found it to be too ethically fraught. But it really raises a lot of these questions about trust and care in our collaborative networks. I withdrew from the technologies due to a lack of care and a lack of trust in what it was doing. I could not find (at the time) anything of value in this network. I guess you can’t care about everything, but I suppose that if you can, holding that trust and care should be your aim. Then you are at least prepared for some type of negative result. Maybe if Victor Frankenstein held tha belief that he should have cared for and trusted, in some manner, his creation then he would have understood its response better.

The FaceAPI Javascript module I used was ported for use in P5JS by the community group ML5js.org. This module is trained on images of faces to detect and predict the location of landmarks on people’s faces (like noses or eyebrows or mouths etc.). My initial project idea was to make a poster that would be bespoke to the viewer. Different parts of the poster’s content that rely on number inputs, such as type height or leading or location, would pull the information from values generated by the mapping of the module. That was the initial plan; I had not given the details a lot of thought. It was possible; I had not seen it before, it would be a good showcase of the collaboration.

ML5JS is a progressive and caring community. They are committed to a sort of radical transparency about the work they create and share. They have introduced a version of a biography that they include with each tool to let people interested in engaging with those tools have a fuller understanding of them. For FaceAPI, by default, they did not implement the complete code as it was developed. “The ml5.js implementation of face-api does not support expressions, age or gender estimation.” These aspects of the tool are so flawed in concept and implantation they have chosen to avoid them, but not to retreat fully from the relationship. They have chosen to spend the time and energy to care for the network, to see possibility, to maybe create something of value.

Even with this limited and cared for implantation of FaceAPI I pulled back. I abandoned the network and retreated to ethically solid ground. The first thing I built was the headline function. Using your camera, the module would measure the distance from the bottom point of your top lip to the top point of your bottom lip, and then it would take that value and create a text-height value to apply to the Headline (in this case, it is the placeholder text that reads Headline.) The implications of what I was going to have to do next occurred to me at that point. I was going to have to give values to different measurements from the faces of audience members participating in the creation of the poster. The idea of giving a literal value to aspects of facial features was enough to end the project at that point. I could find no value in the algorithm. Its flaws seemed unfixable.

I often think about this project. I walked away from it for being a monster in my eyes. My knee-jerk reaction was to pull away and dismiss it as broken and flawed. But what the community at ML5JS does is more like the trust and care, the careful and caring trust, that I have come to embrace in my current work with machine learning. They have worked with technology; they have cared for it and made it better. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke once wrote, “Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.” I often think about this project, and I think about that idea of dragons that are really princesses, of monsters that actually just waiting for us, but unloved—and I wonder about the dragon I saw there and feel like I need to try again. I need to be open to the possibilities that come with keeping doors open, even just a crack.

The end.

︎︎︎︎︎

Next

Chapter 5 — Floating on Oceans.