Chapter 8

Speculative Anthropology.

I can’t help but dream about a kind of criticism that would

try not to judge but to bring an oeuvre, a book, a sentence, an idea to life;

it would light fires, watch the grass grow, listen to the wind, and catch the

sea foam in the breeze and scatter it. It would multiply not judgments but

signs of existence; it would summon them, drag them from their sleep. Perhaps

it would invent them sometimes—all the better. All the better. Criticism that

hands down sentences sends me to sleep; I’d like a criticism of scintillating

leaps of the imagination. It would not be sovereign or dressed in red. It would

bear the lightning of possible storms.

— Foucault, Michel. “The Masked Philosopher.” Ethics:

Subjectivity and Truth. The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984,

Vol. 1. Ed. J. Faubion. Trans. Robert Hurley et al. Harmondsworth: Penguin,

1997. 323. Print.

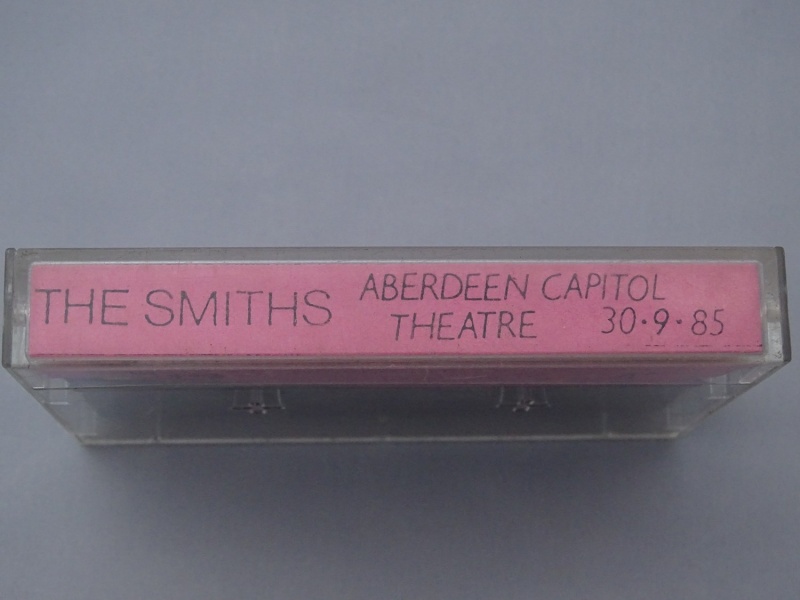

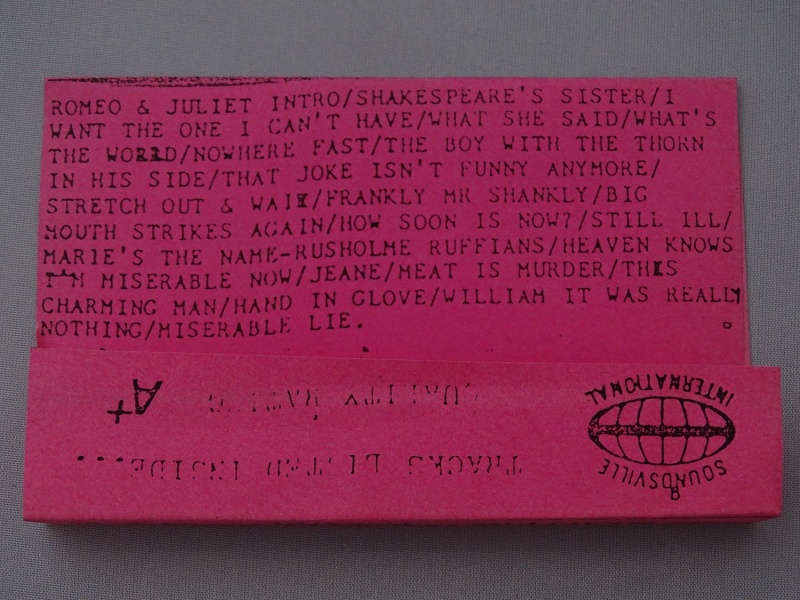

When I was growing up in Toronto, the West End of Queen Street was the very coolest place I had ever been. All the good record stores, vintage clothes, comic shops, they were all there (this is probably not true), and as far as I knew as a 14-year old that liked sort of obscure music and movies, this space was magical. The record store that I loved the most was Penny Lane records, it was a little further out of the way, but they had a rack of cassette tapes that made them worth all of the trips. These tapes, as far as I know, could only be purchased here. They were all bootleg recordings of live shows. The quality of the tapes was something only a real fan could look/listen past. They sounded like the worst version of the worst live album ever recorded. Conversations of the audience members near the bootlegger, the recordings just stopping and starting for reasons I would never know, the sound picked up on a recorder small enough to smuggle into the show, these all added to the magic of these recordings. These recordings were not for everyone. These would never play on the radio (maybe very cool college radio); no one’s cool aunt could buy this at the HMV. These recordings were special to me. I loved these tapes. My favourite band, The Smiths, had broken up when I was 12 years old. I had just missed them by a couple of years. Listening to the live shows on these hilariously bad recordings made me feel special, and like I could have some sort of connection to this band, this show, these other fans that was more personal and meaningful. When I started working with generative machine learning models, I felt the same sort of rush of discovery and connection. Where others saw an ugly melty failure, I heard/saw/felt the bootleg tapes. It was all there, but not perfect in the way a commercial work would be expected to be, it was slightly out of register, with a few typos, with some parts crossed out, it mumbles some words, it felt like a connection, a conversation, and it felt a little like magic.

This work relies primarily on a network of machine learning tools to create the outputs. These text-to-image tools rely on a collaboration with the human to be a source of ideas, interests, and questions. At its most basic level, I input my prompt into a text field, and then the massive network creates images. This network does not rely on my abilities or skills in graphic design to generate outputs, nor does it really need any programming understanding to function. It simply requires me to communicate with it.

I had worked with text-to-image models on previous projects, and they produced some compelling work. They functioned like automatic drawing in many ways. They required a lot of the audience, asking that they find something of value and meaning inside of something that would appear to be effectively meaningless. These earlier attempts were like reading a book of poetry in a language you did not understand, parts of the structures and shapes might be intriguing, but the intention could never be parsed. The new network VQGAN + CLIP was like a Rosetta Stone. What seemed like an impossible or at least improbable idea was suddenly accessible.

Then, at the time, non-profit OpenAI published two project announcements in January 2021, CLIP and Dall-e. CLIP was a new kind of detection model that could caption images very well, and it could do it using a very new method called “zero-shot learning”. Zero-shot means that CLIP does not have to have been trained on a particular data-set to work. One-shot and Few shots are given a starting place to learn from. CLIP can caption images it has never “seen” before.

VQGAN was developed by Patrick Esser, Robin Romback, and Björn Ommer at IWR Heidelberg University in December 2020. It can make new high-resolution images based on image data. This model was important because it used a technique thought to be only applicable for language models and applied it to images, which resulted in much larger resolution images that could be more complex.

Katherine Crowson and Ryan Murdoch both, separately, combined the two models to have CLIP guide the image generation of VQGAN through a text prompt. This allowed for a massive step forward in the quality of text-to-image technology in its ability to output higher quality images and to better understand the text prompts provided. This moved from the completely alien abstraction of early GANs to something like a confused conversation between agents capable of conversations, but really far away, slightly out of tune and out of register in ways that I don’t understand.

“CLIP is a model that was originally intended for doing things like searching for the best match to a description like “a dog playing the violin” among a number of images. By pairing a network that can produce images (a “generator” of some sort) with CLIP, it is possible to tweak the generator’s input to try to match a description.” (@advanoun)

One of the reasons that VQGAN was such a big deal was that it allowed for larger images to be used in the process without using massive amounts of computing power. The challenging thing to understand about these image-generating models is the scale. If you take a tiny image, say 10px by 10px, you are looking at a matrix of possibilities that is 10x10x3 (each pixel mapped to a location that can be in any one of three colors or a combination of those). Each of these possibilities creates a level of complexity. By using a technique called Transformers it allowed for larger images to be created and the complexity and scale of the universe of possibilities to be easier navigated. While it was still massive, this “latent space” could be mapped metaphorically. The multidimensional space that holds all of the possible iterations of a model is like a small galaxy, maybe a small universe. The complexity can hold almost everything. While I can understand and navigate a 3D space pretty well, and 4D space gets a little trickier, and 5D space becomes an interesting thought experiment, the shape of these latent spaces in 512D space means almost nothing to me. It is so far away from my ability to consider it to be gibberish.

This collaborator, this other someone or something that we are communicating with through massive space and with strange translations, they are something very close to alien. The way that value is assigned to aspects of images or language has nothing to do with how I understand it, nothing to do with logic or syllogisms. The collaborator cannot “show me the work” in a way I can appreciate any more than the ocean can explain to the surfer what the meaning and reason behind the next rising wave might be.

One of the more famous GAN’s is called StyleGAN. Developed by Nvidia, it can create life-like images of peoples faces that are so convincing that you can usually only tell it is generated and not a photograph is by looking at small edge details around the hair and background of the image or maybe around where someone’s glasses sit on the ears. Inside of the latent space of this GAN is the possibility of every face of every person ever. Future and past, it contains every single one. We would just need to search for a long time to find a particular someone. The paths that we travel along the 512D space as we create a new set of images with its near-infinite branches of the latent space where maybe everything ever can be found if we looked long enough and hard enough, or perhaps just got lucky. I propose considering the latent space of these models as a sort of way to look at everything that might have been or might be. A view into possible worlds, alternate timelines, multiple universes. If every choice creates a new branch of possible worlds, then everything is possible. This is a sort of speculative fiction, or science, or philosophy. This project aims to consider this idea seriously as a starting point or prompt to explore that unknown space and those possible timelines.

These explorations of the latent space suffer a similar problem of the bootleg tapes of Smiths concerts I would listen to. They are low quality; they are messy, out of tune, raw and strange. But like those recordings, they feel essential and alive, full of possibility and energy and passion. Like old camera and film technologies, the images are not “perfect” representations of the asked-for thing, but I think it is a mistake to see that as the measure of value in this case. The technology will get there soon; the thing described will be generated in a photorealistic and pixel-perfect representation, but doing so will become flat and dull without nuance and voice. The messiness expresses something vital and exciting in my view. I want to talk with this network and ask them to make music and art and gig posters for my favorite bands with me. The fuzziness (meltiness, out of focus, etc.), its messiness provide a sense of honesty and realness that is affecting. The misunderstandings and confusions, the disagreements create a sense of real-life, meaningful communication between agental beings.

I am going to talk to it about things that matter deeply to me, things that I “know” in lots of ways, songs that I have heard a thousand times, I know the music, but I also know the feeling of listening to the album, the way it evokes feelings about my best friends and crumbling family life in my teenage years. It is not a measurable and data-driven knowing that I am sharing; it is something else than that, maybe everything else. These are things I care for, things that I love, the things that made me who I am in many ways.

And while maybe there are more significant concerns and uses of this network of technologies, they are not my interests. When I met HAL, I did not want to talk about questions of phenomenology. I wanted to make cool posters and start a cover band.

This project’s outputs have been expansive. It has produced hundreds of posters, which was my primary aim at the start, poetry, song titles that led to lyrics that led to songs being recorded, music videos, short movies, and poetry recitations by AI-generated performers. Each of the output types used a different network of collaborators and different methods to produce the results.

The posters were created using various text-to-image models but primarily Latent3Visions: CLIP+Taming.ipynb developed by Ryan Murdoch running on Google Colabs. After setting up the needed libraries and support programs, I input my text prompt into a text input field and assign a weight to that input. This “weight” is sort of how much attention the program should pay to this input. If the input was something like “a painting of a loaf of bread by Hannah Höch” with a weight of 1, then the image would trend towards those words as a focus but also pay attention to other connections the network might make. This weight function for this input has a range of -5 to 5, where a negative number seeks to ignore the input. In the case of the above prompt, whatever the opposite of bread and collages are would be produced. Maybe a 3D architectural model of a fish. I can then add secondary text prompts to flesh out the details that my first statement does not contain. For the example prompt, I am might include “collage, flat, baking, kitchen, torn paper, juxtaposition,” and then I assign a weight to this as well. Past the first text prompt, these are not mandatory inputs.

The following inputs are image-based. If I wanted to narrow the vector of paths through the latent space, I could give the model an image to refer to. Any image can be pointed to and given a weight value. I can also provide a negative image value to stay away from. This sort of prompt and weighting is the primary starting place for most of these GAN’s. Additional information such as learning rates, decay numbers, height, width, and the total number of iterations is added in various ways depending on the system. Most of the GANs can be left to generate images, some have additional steps and needs, but generally, that is all that is needed.

The language-based outputs such as poems and song lyrics were generated in collaboration with GPT-3 developed by OpenAI. I was granted access to the closed beta through an open application process. The GTP-3 beta is accessed through a website but has similar prompts and weight input fields. After setting initial values, I simply frame my text prompt. The following is an example of the prompts:

Lyrics to The Smiths song “How can she find time to be so unkind?”

Lyrics by Morrissey

Verse 1:

That would be enough information to give the program-specific points of interest and a structure to refer to.

GPT3, in this case, responded with:

Lyrics to The Smiths song “How can she find time to be so unkind?”

Lyrics by Morrissey

Verse 1:

I was amazed to hear her say,

That she thought that I’d be pleased to know

That she had started seeing someone new,

And just how happy he made her feel.

Chorus:

How can she find time to be so unkind?

When I’m feeling so lonely in my mind.

How can she find time to be so unkind?

When I’m feeling so lonely in my mind.

Verse 2:

I was shocked to hear her say,

That he had been round to meet her folks,

And they liked him, but they’d never quite seen him before,

And she said that they could really be a couple.

The system uses a complex method of language understanding called “attention” that allows the model to assign values to each word in the prompt and to create a matrix of these values that allow the model to diagram the sentence in a way (it is not using this structure really, but it is a close metaphor for what it is doing). With this ability, it can look backward and forwards to words it might generate and has generated and measure the fit of those words.

These tools are not for just one thing. Aimed at different problems, they are capable of solving all sorts of issues. Ideas intended to solve language problems can be applied to images, to music, to probably anything. A brick has many uses, building walls or bridges, propping open doors, smashing windows. Maybe all tools are this kind of multiple, but it takes a sort of imagination to figure those uses out.

The digital nativeness of machine learning might be why this network of tools and ideas can be so multiple in its uses. The limitations of imagination that surround our current modern digital tools (Adobe CC suite) might be because they are often trying to solve a physical, pre-digital world problem with computers. They are an attempt at a translation that is limited by both the original nature of the thing and the constraints of this new one. These machine learning tools are not trying to solve a single and existing problem using new methods and technologies. They are instead a new way of thinking about the world.

My process then for this project has been to attempt to trust these networks of collaborators with these things that I care deeply about. To have amazing, frustrating, funny conversations with this alien someone. These conversations are complex; they are multilayered, with stops and starts that make things rough in a way that the modern world of polished interactions tries to smooth over with simple and clean interfaces, interactions, and design. My sides of these conversations have been prompts that are often along the lines of “A RoboCop movie poster in the style of Armin Hofmann” or “A Point Break movie poster by Hanna Höch.” They are a mixture of things I loved in my youth asked to be reframed and reconsidered through the lens of the things I care about in my adult life.

This project has been one of partnerships and collaborations. I have had what feels like (and maybe is) conversations with a network that I am only a part of. The outputs have been meaningful to me. I have had to spend time considering the network’s, often unexpected, responses. The process has also clarified the nature of these networks for me. While machine learning models are the most obvious example of an agental tool, their abilities so obvious, it more than anything shows that this shifting of perspective should be applied to how we see all of the tools we “master” and how we view our roles in the creative network of tools, ideas, people, objects, and all of our collaborators (human and non-human.)

When I was working at Rhode Island School of Design, I overheard a graphic design student say that they had “made a book.” I have been thinking about this statement for a long time, and on and off, I reconsider it. What does it mean for a designer to “make a book?” This student did not make the paper, the ink, the typeface, the historical structures of classical page shapes and margins; they likely did not write the text; they may have sewed the signatures (having learned the skill at RISD). So then, what does it mean to say that we “made a book.” Like any cultural creations, they are not made whole-cloth, pulled from our imaginations fully formed and wholly original. They are a collection of culture, a circle drawn around a selection of everything, that is then presented as a made new thing. Without considering what those points we have circled mean, we might think that we are the ones in charge, that the drawing of the circle is the most crucial aspect, that without us to direct these disparate elements they are meaningless and without agency. This project has chosen to consider the collaborators that we believe to be our “tools.” Questioning that relationship and that need to control and master our partners. Considering an alternative to our current thinking and exploring the results of moving away from a need for control and moving towards a place of care and trust. A decentered graphic designer who is part of a network of making, made up of collaborators, human and non-human, that wants to see where we might go if we let go and trust that if we show care for our team, we will end up somewhere great.

The end.